FINANCE

Moving Money Versus Making Money

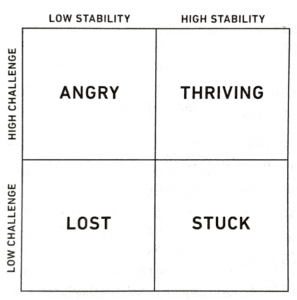

Early-stage businesses rarely produce clean profit. Costs arrive first. Revenue follows later. This pattern of early cash outflows followed by delayed revenue inflows aligns with the J-curve, where losses precede stability. Many founders misread this phase. They wait for net profit before acting. Liquidity dries up. Momentum stalls.

Illscape Studios chose a different frame. The focus stayed on moving money. Cash entered, circulated, and exited on purpose. Across 2025, this approach generated about 40k in revenue from four live events and artist operational solutions, while the business remained pre-break-even. Break-even sits in October 2026.

This blog explains why moving money works, how bootstrapping fits without distorting results, and how lenders actually evaluate early-stage firms. A cultural reference helps ground the idea.

The Cultural Signal in Boyak Yellow

In Cardi B’s 2017 track Bodak Yellow, the line “I make money moves” functions as a statement about agency over cash flow. The lyrics do not describe profit. It describes action. Money responds to decisions, timing, and direction.

Operationally, “making money moves” means moving money, with cash directed, timed, and circulated to sustain execution before profit stabilizes.

Read operationally, the line aligns directly with the concept of moving money. The phrase supports three related interpretations; each tied to cash-flow behavior rather than accumulation.

The lyrics work because they capture the principle directly. Money is not the result. Money is the mechanism. Movement is the work.

These interpretations operate together. Moving money requires control, circulation, and signaling to be managed simultaneously. Illscape applied all three through deliberate cash sequencing rather than waiting for profit confirmation:

- Interpretation One: Behavioral Control

“I make money moves” signals that money follows intentional action. The speaker decides where money goes and when it moves.

In operational terms, this reflects active cash direction. Funds are allocated toward deposits, production, and execution before profit stabilizes. Movement precedes margin.

- Interpretation Two: Liquidity Over Accumulation

The emphasis sits on motion, not possession. Money has value because it circulates.

In operational terms, this mirrors cash velocity. Liquidity depends on shortening the time between spending and collection. Cash held idle does not support execution. Cash in motion sustains operations during the J-curve phase.

- Interpretation Three: Strategic Signaling

Repeated movement signals credibility. Flow itself creates leverage and access.

In operational terms, consistent cash movement produces observable patterns. Lenders, partners, and vendors respond to predictable inflows and disciplined outflows, even when net profit remains thin.

Define the Terms

Making money usually means net income. Revenue minus expenses produces profit on an income statement.

Moving money focuses on timing. It centers on when cash enters and exits, and how long cash is unavailable during operations.

Corporate payments literature uses similar language. CGI’s report title, “Making Money from Moving Money,” describes economic value created through payment flows and services tied to cash access, timing, and transaction infrastructure. The phrase originated in financial services, yet the operational logic applies to small creative firms.

Why Early-Stage Firms Prioritize Movement

New firms often sit inside a J-curve pattern. Kenton defines the J-curve as a trendline with initial loss followed by later gains, frequently seen in turnarounds. Early losses come from setup costs, learning curves, and small scale. Waiting for clean profit during this phase can delay necessary operating learning.

Churchill and Mullins highlight a core risk: growth consumes cash, and firms can run short on cash even with strong products. This risk hits creative businesses early because they prepay costs, then collect later.

Cash Conversion Cycle & Creative Operations

Hayes defines the cash conversion cycle as the time required to sell, collect receivables, and pay bills. It notes shorter cycles keep cash tied up for fewer days. Event operations map well onto this logic, even without inventory. During this phase, waiting for margin delays execution. Cash still funds deposits, payroll, marketing, and production. Firms that manage timing last longer.

Event-cycle translation:

- “Inventory” becomes production commitments, marketing spend, and deposits.

- “Receivables” become ticketing receipts, sponsorship payments, merch settlements, vendor settlements, and service invoices.

- “Payables” become venue settlements, contractors, production vendors, and artist guarantees.

Leadership improves cash position by pulling inflows forward and pushing outflows later, within ethical and contractual bounds. Hayes notes that the cash conversion cycle (CCC) shortens when a firm collects faster and pays more slowly while maintaining obligations.

Cardi B’s Bodak Yellow frames money as an active instrument rather than a passive outcome. The refrain “I make money moves” emphasizes direction, timing, and control over cash. In managerial terms, this aligns with cash flow as a tool for execution. The operational reading strips away consumption narratives and centers on sequencing, allocation, and liquidity.

A useful translation:

• Pop culture: money signals momentum and leverage.

• Management: cash flow signals operational control and survivability.

Practical Mechanisms for “Moving Money”

A serious “moving money” practice looks like working-capital management, not hype.

Mechanism 1: Pre-Commitment

Advance sales, deposits, and retainers shift inflow earlier in the cycle. This reduces reliance on post-delivery collection.

Mechanism 2: Milestone-Based Release

Tie spending to confirmed revenue triggers. Release funds when a threshold clears, not when emotions spike.

Mechanism 3: Payment Terms

Negotiate terms aligned with cash inflow timing. Pay early only when discounts exceed financing cost and risk.

Mechanism 4: Financial Statement Discipline

The U.S. Small Business Administration frames the balance sheet as a baseline tool for tracking capital and supporting cash-flow projections. Leadership needs balance sheet awareness to avoid hidden liquidity risk.

Mechanism 5: Growth Pacing

Churchill and Mullins frame growth pacing as a cash balance problem, not a marketing slogan. Growth pacing protects liquidity when demand rises faster than cash collection.

Bootstrapping & Owner Capital

Illscape bootstrapped during 2025. Owners contributed capital to cover deposits and timing gaps. This behavior aligns with standard small-business practices.

Accounting treatment matters. Owner contributions record as equity, not revenue. The IRS excludes capital contributions from gross income. Financial statements show these funds under financing activities, not operating income.

This distinction protects integrity. The 40k figure reflects only operating revenue collected from ticket sales and business plan writing. Customer payments produced the revenue. Owner capital did not inflate it.

Bootstrapping strengthens liquidity. It extends the runway. It signals commitment. It does not fabricate profit when recorded correctly.

Why Lenders Respond to Movement

Lenders underwrite repayment capacity. They examine cash flow, not stories.

Primary inputs include:

- Bank statements and deposit history

- Cash flow coverage and consistency

- Working capital position

- Trend direction

Net profit matters later. Early-stage firms often show thin or negative profits due to growth investment. Lenders expect this during the J-curve phase.

The Small Business Administration states lenders assess ability to repay based on cash flow, collateral, and equity investment. Owner equity lowers lender risk by sharing exposure. Investopedia describes debt service coverage ratio as a core metric tied to cash flow, not accounting profit.

So, the question of how much of your own money you put in functions as diligence. Owner capital does not negate operating revenue. It supports it. Lenders separate operating performance from financing support.

Movement matters because it produces observable patterns. Predictable inflows paired with controlled outflows reduce default risk. Profit alone does not guarantee liquidity

Case Study: Illscape Studios

Illscape’s 2025 operations illustrate this logic. Four live events and one business plan writing produced around $40,000 in revenue during a pre-break-even phase. Leadership plans eight events for 2026, roughly doubling revenue from 2025, with a projected break-even in October 2026.

This pattern fits early-stage cash-flow reality. Leadership utilized event cycles and artist operational solutions as repeatable units. Each cycle trained systems, improved forecasting, and strengthened working-capital control.

Conclusion

The transfer of funds constitutes the management of working capital applied to real operational activities. It underpins decision-making processes during initial stages when profitability has not yet been realized. Moreover, it aligns with the methodology by which advanced payment systems generate value through movement and access, as evidenced in CGI. Cultural narratives often reflect this theme; however, disciplined operators systematically translate it into structured processes.

References

CGI. (2020). Making Money from Moving Money [PDF].

Kearse, S. (2018). Tracks: “Money” Cardi B. Pitchfork.

Churchill, N. & Mullins, J. (2001). How Fast Can Your Company Afford to Grow? Harvard Business Review.

Hayes, A. (2025). What is the Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC)? Investopedia.

Kenton, W. (2025). J-Curve: Definition and Uses in Economics and Private Equity. Investopedia.

U.S. Small Business Administration (2025). Manage Your Finances.

Moving Money Versus Making Money